Government Deficit – We Have Met the Enemy, and He Is Us

While the government narrowly missed defaulting on its debt obligations, some have asked, “What would the impact be if the government defaulted on its credit?” As a financial professional with more than 40 years of experience, I shudder to think of what may happen in this circumstance. My best thought is the world’s entire financial structure would shake. Economies would collapse quickly into recession, if not depression. Payments would slow/vanish. It may be financial Armageddon.

Government spending over and above government tax receipts is the problem. The title of today’s piece, “We Have Met the Enemy, and He Is Us,” is a quote from an old Pogo comic strip. If you remember Pogo you are of my generation.

The title infers that Americans are the reason we have this issue at hand—that government spending and borrowing have risen dramatically. In a collective sense, we like the government to spend money and don’t like to pay taxes. Now, we may not like the government spending money on certain projects, but we like them to spend money in total, just not on the “other guy’s” programs. And we don’t like to pay taxes, which many believe should be levied on the “rich” or the other guy. Politicians understand this. We have met the enemy—and he is us. We are living in a “fiscal fantasyland” and unless a change occurs, we could face the unwelcome fate of lowered living standards.

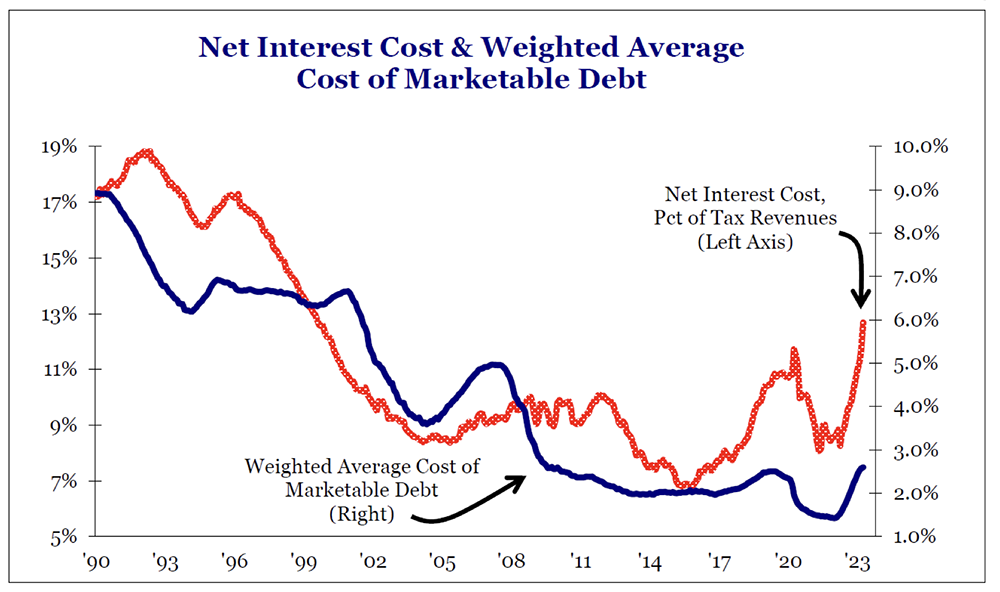

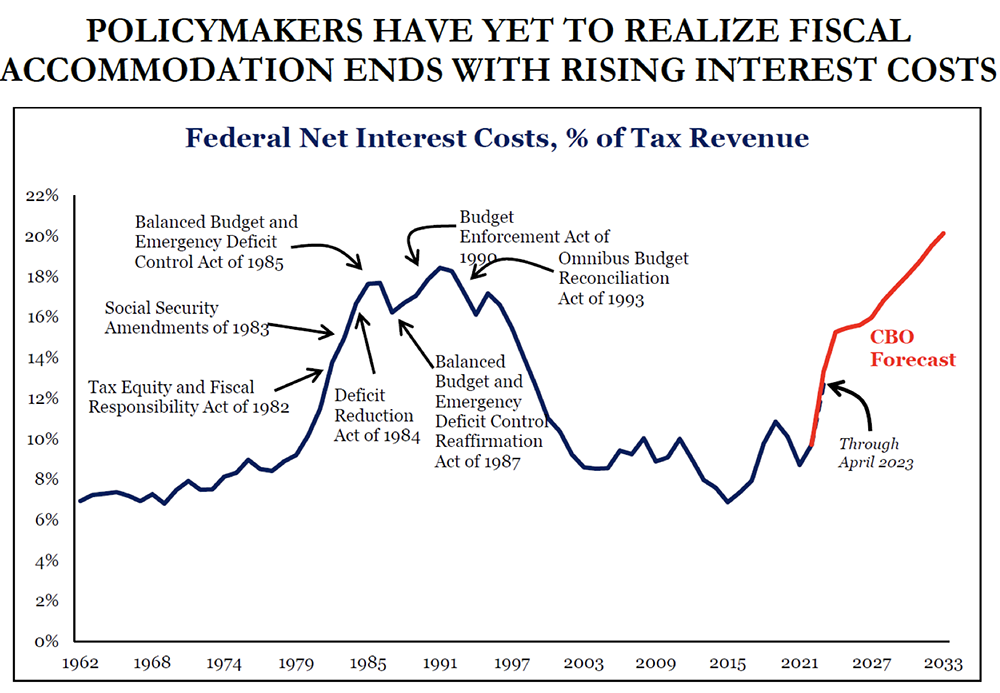

Source: Strategas

An Economist article suggests that unless things change, the U.S. may face federal government deficits of about 7% of national gross domestic product by the end of this decade—a mere seven years away.1 This isn’t government spending levels of 7% of GDP, but the amount they need to borrow to fund spending plans.

Today’s GDP level is about $23.3 trillion.2 Assuming a growth rate of 2% per year (real) over the next seven years, the government will have to borrow $1.75 trillion per year, on average, to finance average net deficits. For frame of reference, deficit spending was $0.45 trillion in 2008. Given this frame of reference, annual deficit expenditures are expected to have risen by 288% since 2008. The only time deficit spending rates have occurred at 7% of GDP in the past were during times of political/economic emergency such as periods of war or deep recessions/depressions.

None of this is new. We have been running ever-increasing government deficits for years (all but a portion of the 1990s). But the growth rate of deficit spending is accelerating. I suggest this level of debt creation by the federal government will, if left unaddressed, be destructive to private sector growth. Something will need to eventually change.

With That Background

All that said, it seems a good time to discuss government deficit spending. While our government can afford to spend more than it takes in, how long can this gravy train run? Will there be a day of reckoning? If so, when? These are valid questions to ask, but the answers are in the wind and speculative. However, the consequences of a default on government payments are so high, so severe that addressing deficit spending is something that needs to occur.

Source: Strategas

The day of reckoning is impossible to predict. In January 2000, the U.S. debt was $5.8 trillion. It was impossible to predict when it would reach $12.8 trillion.3 Nor did it matter in the end. In January of 2010 when the debt reached $12.8 trillion, it was impossible to predict when it would reach $23.2 trillion, nor did it matter in the end.4 In January 2020 when the debt reached $23.2 trillion, it was impossible to predict when debt would hit $31.4 trillion, nor did it matter in the end—so far. But here we are. With national debt outstanding at $31.4 trillion.5 The world’s capital markets have yet to “riot” over the issue.

It all comes down to trust. Our national debt creation rate has been running at a higher growth rate than our national output growth rate. That is akin to a household or a business that continues to lever its balance sheet at a higher rate than its income growth rate. Eventually, deep problems can occur. However, if the markets continue to demand our bonds, trouble is averted. When that level of trust waivers, it may be too late, and the economy could suffer a severe downturn.

So, what should we do? What solutions could help this vexing problem?

Choice #1 – Cut Spending

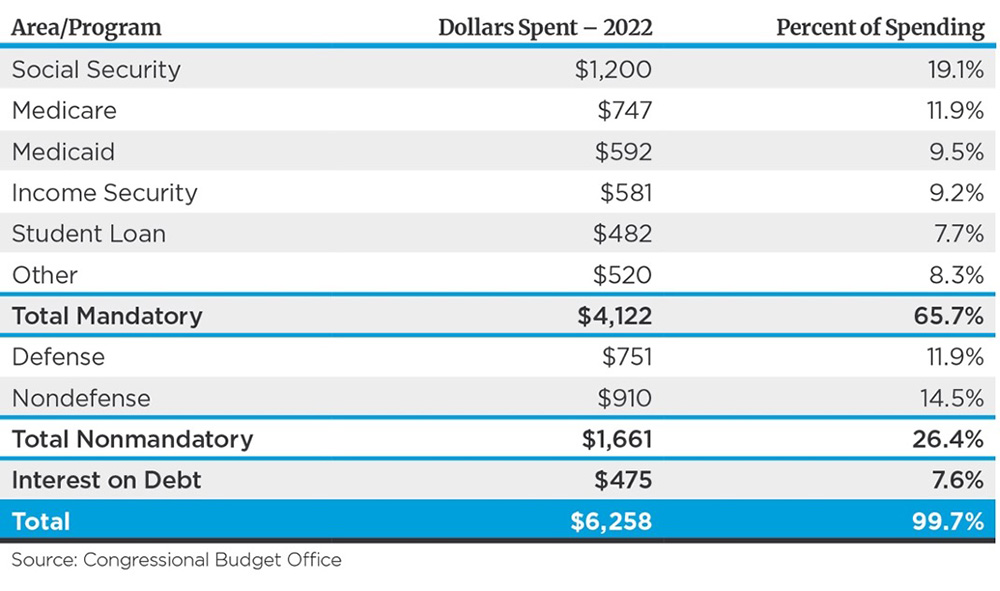

Facing and attacking the deficit through spending “cuts” seems impossible politically and impractical fundamentally. Let’s look at current government spending (dollars stated in billions).

It is interesting to note that a total of 65.7% of money spent by the federal government in 2022 was for “mandatory” items—programs backed by law.6 To change the character of these payments, laws will need to be changed. It is also interesting to note that spending on national defense now represents less than 12% of all spending, and major mandatory social programs outweigh spending on defense by a ratio of 5.5 to 1.7 So much for those who think the government’s number one job is to keep the nation safe.

Unless laws change, in what area can spending cuts actually occur? Only 26.4% of government spending is “nonmandatory.”8 The Congressional Budget Office is forecasting that government spending is scheduled to rise to $8.5 trillion by 2030, and government debt outstanding will rise from $25.7 trillion to $38.6 trillion over that short, seven-year period, an increase of debt outstanding of 50.7%.

Over that seven-year period, the nation’s population will continue to get older, as more baby boomers retire and start to draw Social Security and Medicare benefits. Of course, these programs are the political “third rail” that politicians won’t touch. That bias takes about $2 trillion in current spending off the spending-cut negotiation table. Additionally, the government shouldn’t default on interest payments, so that takes another half-trillion off the table. While defense spending isn’t classified as a mandatory budget item, most Americans believe national defense to be one of the main reasons governments exist in the first place. So, we can rationally take that item off the table—at least in total.

That leaves about 50% of the budget up for grabs to find cuts. If politicians can’t or won’t tackle the issue in any mandatory spending area, then that leaves us with less than 15% of spending classes that may be cut (nondefense, nonmandatory areas). So there appears to be little wiggle room for major spending cuts to occur unless some hard decisions are made.

Choice #2 – Raise Taxes

Another alternative that is politically unpopular in many circles is for the government to raise taxes to pay for additional spending as we move forward. Many politicians like the idea of raising taxes—driving people to pay their “fair share,” whatever that means. We have all seen the data that the U.S. income tax system is one of the more “progressive” in the developed world. This is flatly undeniable, as upward of 40.1% of all households pay no income tax, and the top 10% of earners paid 74% of all income taxes.9 This data does not include state, local or employment (Social Security) taxes.

What of corporations? Don’t they pay much of the tax burden? Well, not really. According to data from the Treasury Department, individual taxpayers paid $1.4 trillion in taxes (52% of total federal government revenue) and $923 billion in Social Security and Medicare taxes (34% of total federal government revenue). Corporations paid $221 billion in taxes (8% of total). The remainder was paid by various duties, fees, etc.

I also subscribe to the economic view that, by and large, most government spending programs act as simply a redistribution of society’s wealth. Most government spending does not create long-lasting, sustainable economic growth. Moving money from one person’s pocket to another’s may be socially desirable in some circles, but that redistribution does not create sustainable economic growth. Consequently, as government spending as a percentage of overall economic activity increases, economic growth, opportunity and societal wealth creation tends to weaken.

Low levels of economic growth will probably accompany the solution of rising tax bills no matter who is to pay them.

People believe they are already highly taxed. There is some validity to this belief. Compared to the size of the economy (GDP) in 2021, federal tax receipts were the highest the U.S. has experienced in the last 75 years, since the days of World War II. In 2021 tax receipts as a percent of GDP were 13.6% higher as a percent of GDP than they have been on average since 1945.10 But that doesn’t mean they can’t go higher.

Simply raising taxes to address the deficit issue isn’t a solution but a partial solution with attached economic trade-offs.

Choice #3 – Inflate the Problem Away

This isn’t a painless solution to the problem and comes with real issues. The higher the income level, the easier debt repayment is for a borrower to handle. One way of increasing tax revenues is to inflate national incomes through broad price increases (inflation). Under this scenario, the dollars borrowed by the Treasury that come due for repayment in 10 years will be easier to handle if revenues rise rather dramatically. This can be handled by not increasing taxes but by taxing ever-higher incomes that are being driven not by economic growth but by a rise in the general pricing environment (inflation).

Of course, there is a price to be paid that accompanies this “solution.” Societal wealth destruction can take place, the value of the dollar to other currencies probably declines and business cycles probably become shorter and more volatile. Besides, if inflation is high, high interest rates will follow. This simply irritates the deficit problem as ever-higher interest payments occur.

Choice #4 – Print Money to Pay the Debt

Some suggest that government deficit spending and the issuance of seemingly unlimited amounts of debt will have little to no negative effects on the economy as described in MMT (modern monetary theory) concepts. Have the government—through the Federal Reserve and other agencies—simply buy the new, higher levels of debt. As long as the dollar is the world’s preferred “reserve currency,” the markets can absorb this strategy. At least that is how MMT thought goes.

We have found this theory flawed, as money supply (as measured by M2 growth rates) rose dramatically from 2020-2021 during the pandemic period. This period of monetary supply explosion was followed by the most rapid increase in inflationary pressure we have seen in more than 40 years.11 The “printing” of money matters, after all. Milton Friedman’s monetary school of thought retains validity. Government spending, borrowing and taxing all have consequences. Perhaps some of the consequences are unintentional, but they occur nonetheless.

Choice #5 – Grow Our Way Out of the Problem

This is probably the most economically sound solution to the deficit issue. As the economy grows (“real” incomes rise), tax receipts tend to rise as well. The problem with this solution is that it may require the government to retreat from actions broadly backed by those who believe the government is in existence to centrally “control” activities.

In other words, this solution flies in the face of an ever-growing government presence. Remember my bias that government does not create true, broad-based economic growth? Only the private sector can accomplish this goal. Income multipliers tend to be negative for government spending and positive for private sector growth. Read Dr. Robert Barrow’s (Harvard) work on this subject.

In the End

In the end, the solution to the deficit problem won’t be painless. Many will have to pay the price. But if the problem is addressed quickly and thoughtfully, I believe we will find the solution to be easier to handle than to just let the problem fester.

I fear if the deficit problem is left alone, the capital markets will eventually riot, which will harm everyone to one degree or another. Then, in the end, it will matter.

Sources:

1“Governments Are Living in Fiscal Fantasyland”

2St. Louis Federal Reserve

3,4,5One River Asset Management

6,7,8Congressional Budget Office

9Statistica Data

10,11St. Louis Federal Reserve

This commentary is limited to the dissemination of general information pertaining to Mariner Wealth Advisors’ investment advisory services and general economic market conditions. The views expressed are for commentary purposes only and do not take into account any individual personal, financial, or tax considerations. As such, the information contained herein is not intended to be personal legal, investment, or tax advice or a solicitation to buy or sell any security or engage in a particular investment strategy. Nothing herein should be relied upon as such, and there is no guarantee that any claims made will come to pass. Any opinions and forecasts contained herein are based on the information and sources of information deemed to be reliable, but Mariner Wealth Advisors does not warrant the accuracy of the information that any opinion or forecast is based upon. You should note that the materials are provided “as is” without any express or implied warranties. Opinions expressed are subject to change without notice and are not intended as investment advice or to predict future performance. Consult your financial professional before making any investment decision.

Mariner is the marketing name for the financial services businesses of Mariner Wealth Advisors, LLC and its subsidiaries. Investment advisory services are provided through the brands Mariner Wealth, Mariner Independent, Mariner Institutional, Mariner Ultra, and Mariner Workplace, each of which is a business name of the registered investment advisory entities of Mariner. For additional information about each of the registered investment advisory entities of Mariner, including fees and services, please contact Mariner or refer to each entity’s Form ADV Part 2A, which is available on the Investment Adviser Public Disclosure website. Registration of an investment adviser does not imply a certain level of skill or training.